Radioembolization is a minimally invasive, cutting edge form of cancer treatment. This procedure is commonly known as Y90 since it relies on a substance called Yttrium-90. In other words, Y90 radioembolization is an outpatient procedure where tiny radioactive beads are injected into small blood vessels supplying liver tumors through a catheter. This catheter is inserted into a blood vessel in the leg or wrist through a pinhole in the skin. Using live x-rays for guidance, a catheter can be maneuvered into the exact blood vessel supplying tumors, the radioactive beads can be injected into the catheter, and the tumors can be treated. This is an outpatient procedure so our patients usually go home later in the day without any incisions and without any of the side-effects from systemic chemotherapy.

Indications for Treatment

Radioembolization is a potential option for any patient with liver tumors. It can be used in conjunction with chemotherapy or can be a stand-alone treatment. It is an option for primary tumors (which start in the liver such as hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma) and metastatic tumors (which travel to the liver from some place else in the body such as colon cancer, rectal cancer, breast cancer, or neuroendocrine tumor). It can be used as first-line therapy, second-line therapy, third-line therapy, or for palliation. It can be used in an aggressive fashion very early during treatment or as a last resort when other options have failed. Each patient, each tumor, and each situation is different and therefore, the role of Y90 in each patient’s treatment can also be different. The Y90 process initially begins with an outpatient visit with one of our physicians. During this visit, we are able to discuss your current disease state and goals of treatment. A picture is worth a thousand words and specializing in image-guided medicine allows us to review your imaging together. We work closely with your oncologist to determine your candidacy for the procedure based on the type and amount of tumor you have, the location of your tumor, and the status of your liver, and your overall health.

Procedural Details

Shortly after your initial visit with us, we arrange for the performance of a "mapping" angiogram at Albany Medical Center. This outpatient procedure provides us with helpful information in order to determine your candidacy for treatment, to plan for that treatment, and to provide data needed to calculate an individualized dose of therapy. The mapping procedure is actually very similar to the treatment procedures. First, a small catheter is introduced into either the femoral artery (in your groin) or the radial artery (in your wrist). This catheter is navigated under x-ray guidance into the arteries bringing blood to the liver. When the catheter is appropriately positioned, x-ray dye (contrast) is injected and images are obtained. These images allow us to "map" the vascular anatomy of the liver. Sometimes, the blood vessels supplying the tumor are in close proximity to normal blood vessels supplying your stomach and intestines. If that is found to be the case during the mapping procedure, then we typically block the flow in (embolize) those arteries in order to protect your stomach and intestines.

After the mapping process is complete, we inject a small radiotracer into the blood vessel supplying the tumor. This is the blood vessel we intend to inject the radioactive beads into on a future day. We then bring you to our nuclear medicine department where we have special cameras that can detect where this radiotracer traveled. This serves as a “dry run” of the treatment and allows us to predict exactly where the Y90 will travel. It specifically allows us to determine the amount of the Y90 that may pass through the liver and end up in the lungs. This is an important piece of information for us to know because too much of this shunting between the liver and lungs can put your lungs at risk for radiation injury during treatment.

In the subsequent week or so, we, together with our colleagues in Radiation Oncology, use all the information gathered from the mapping procedure along with the pictures we acquired from the nuclear medicine cameras to do an in-depth analysis and calculate the exact dose of radioactive beads suitable for treatment. It is our utmost priority to determine a personalized and precise dose that is both effective for treatment but also safe and easy for your body to tolerate.

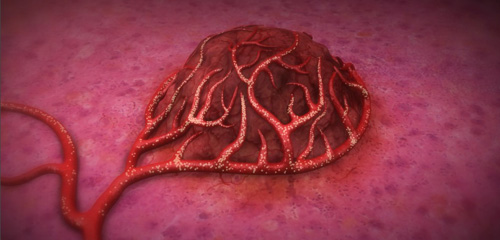

On the treatment day, you return back to Albany Medical Center. The day begins in our recovery room followed again the procedure performed in one of our interventional angiography suites. This time, however, we already have a plan in mind. We are able to place a catheter directly into the exact blood vessel supplying the tumor. Instead of injecting a radiotracer, we inject the Y90 this time. You will see people from our Radiation Safety office monitoring the injection as it is delivered. When the Y90 beads are injected, they eventually lodge within the tiny blood vessels inside the tumor. Over the next 2-3 weeks, they deliver a small amount of radiation that travels only 2 mm away from the injected particles. This radiation is able to treat the tumor while preventing the typical side effects of systemic therapies. There are often two treatment days since we like to treat each half of the liver on separate days.

This pictures demonstrates the Y90 microspheres traveling into the blood vessels surrounding and bringing blood to a tumor (www.sirtex.com).

Recovery

Following delivery of the Y90 microspheres, you proceed to our recovery room for monitoring for a few hours. Almost all of our patients will go home on the day of treatment. It is very common to have a week of fatigue following the treatment. Some patients will also report some mild discomfort in the upper right side of the abdomen along with a decreased appetite. Other patients will feel perfectly fine without any side effects from the procedure. Potential but rare effects of Y90 include liver damage and the development of an ulcer in either the stomach or small intestine. Ulcer formation is rare but the risk of this occurring is one of the things we assess on the day of the mapping angiogram. If we believe that there is a possibility of the Y90 microspheres making their way into the arteries of the stomach or small intestine on the day of treatment, then we will block the flow in those arteries for your protection. This reduces the risk of ulcer formation. These ulcers, if they occur, can often be treated with medication.

Once you are our patient, we believe it is extremely important for us to be proactive and engaged in your care. Therefore, we will help you make arrangements to see us in our office 1- and 3-months after treatment. We then like to see you every 3 months for the first year. At that time, we obtain imaging to monitor the status of the tumor in your liver so that we can work with your oncologist to alter the treatment strategy as needed.

Results

It has been shown that radioembolization can be an effective treatment for several different types of tumors. In particular, radioembolization can be used successfully to treat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In 2010, Salem et al published their results after treating 291 patients with HCC. Response rates to radioembolization were 42% and 57% according to World Health Organization (WHO) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) criteria, respectively. The time to progression after Y90 was 7.9 months. Child-Pugh A patients had better response rates than Child- Pugh B patients with median survivals of 17.2 months and 7.7 months, respectively. Hilgard, et al performed a study evaluating 108 patients with HCC treated with radioembolization. They demonstrated outcomes that were equivalent to chemoembolization with a response rate according to EASL criteria of 40%, a time to progression of 10 months, and a median overall survival of 16.4 months. Radioembolization has also been shown to be a safe and effective option for patients with HCC and portal vein thrombosis. In 2016, de la Torre, et al. performed a comparative, retrospective analysis in patients with HCC and portal vein invasion receiving treatment with radioembolization or Sorafenib. This study demonstrated a median overall survival of 8.8 months in the patients receiving radioembolization compared with 5.4 months in the patients receiving Sorafenib. Edeline, et al also reported their experience with HCC and portal vein thrombosis in 2016. They found that the median overall survival in the patients treated with radioembolization was 18.8 months vs. 6.5 months in patients treated with Sorafenib. In 2015, Kokabi, et al performed an open-label prospective study of the safety and efficacy of radioembolization in patients with HCC and PV thrombosis. In this study, the median overall survival was 13 months with a TTP of 9 months.

For patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, several studies have been done to demonstrate the results of Y90 therapy when used adjunctively or together with chemotherapy. Van Hazel, et al reported the results of the SIRFLOX study in 2016. In this study, 530 patients were randomly assigned to receive first-line treatment with mFOLFOX6 or mFOLFOX6 plus radioembolization. This study demonstrated that the addition of Y90 improved the median progression free survival in the liver (12.6 vs. 20.5 months), the objective response rate in the liver (68.8% vs. 78.7%), and the percentage of patients with their first progression in the liver (77% vs. 52.4%). Similarly, in 2010, Hendlisz, et al reported the results of their randomized study evaluating chemotherapy with and without radioembolization. They demonstrated improvements in the time to liver progression and overall survival. These studies confirmed the results of earlier studies, which have shown that radioembolization plus systemic chemotherapy can lead to improvements in progression free survival and overall survival. Radioembolization has also been used successfully in the salvage setting, when progression continues despite several lines of chemotherapy. For example, Saxena et al reported their results on 302 patients in 2014. They reported that in patients who underwent one previous line of chemotherapy, a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) was seen in 43%, stable disease (SD) was seen in 29% and progressive disease (PD) was seen in 26%. The median survival in this patient population was 12.0 months with 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month survival rates of 70%, 49%, and 27% respectively. In patients receiving two previous lines of chemotherapy, CR or PR was seen in 35%, SD was seen in 37%, and PD was seen in 24%. The median survival in this patient population was 10.5 months with 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month survival rates of 69%, 40%, and 20% respectively. In patients receiving three or more lines of chemotherapy, CR or PR was seen in 23%, SD was seen in 29%, and PD was seen in 40%. The median survival in this patient population was 5.6 months with 6-month and 12-month survival rates of 47% and 21% respectively. In 2012, Bester, et al. reported the results of their study in which they compared the outcomes of 224 patients with colorectal liver metastases that were unresponsive to chemotherapy with the outcomes of 29 patients receiving medical therapy or best supportive care. The median overall survival was 11.9 months in the radioembolization group compared with 6.6 months in the standard-care group. In 2011, Nace, et al reported their data on 51 patients who had failed two lines of chemotherapy and found that the median overall survival was 10.2 months. Of note, they found that the median overall survival was 17.0 months if there was no disease outside of the liver.

Radioembolization also has a role in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumor. In 2014, Devcic, et al reported the findings of a metaanalysis on the efficacy of radioembolization to treat metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. They evaluated 12 studies and found an objective response rate (CR+PR) of 50% and a disease control rate (CR+PR+SD) of 86%. The median overall survival was 28.5 months. Memon, et al, in 2012, reported 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year overall survival rates of 72.5%, 62.5%, and 45% respectively. Guidelines regarding the role of intraarterial therapies in metastatic neuroendocrine tumor from the NET-Liver-Metastases Consensus Conference were published by Kennedy, et al in 2014. This paper concluded that the majority of patients receiving this therapy experience improvements in hormonal syndromes and the symptoms caused by the disease burden.

Recent data has also shown that radioembolization may play a role in the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Recently, two large retrospective series evaluating the role of radioembolization in breast cancer have been published. The first is by Fendler, et al. In this study, the authors noted a 30% decrease in maximum standardized uptake value for up to 5 treated lesions in 52% of patients on follow-up PET CT. In this study, a transaminitis and increased liver tumor burden were associated with worsened survival; these are favorable for Heather at this time. Pieper, et al reported their results in 44 patients. They found a partial response rate of 39.5% with a worsening performance status being a poor prognostic sign; this too is favorable in Heather. Several other case series have been published in recent years, which have shown a median overall survival of 9-14 months in patients with <25% tumor burden in the liver (which is the case with Heather). In addition, these studies have shown that patients with stable extrahepatic metastases can benefit from liver directed therapy. Finally, these studies have shown partial response rates of 47% by WHO criteria and 26-61% by RECIST criteria.