Indications

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common condition affecting middle and older age males. As the prostate enlarges during a man’s life, it can compress the urethra and cause lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Some of the more common LUTS include increased urinary frequency, difficulty starting urination, weak or interrupted stream, as well as urinary retention. First line therapies for BPH include lifestyle changes and medications. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is the gold standard for surgical management of patients with moderate LUTS and moderately sized prostate volume (60-80 mL). In patients with larger prostate sizes, open prostatectomy may be performed [1]. Although TURP and open prostatectomy produce very good functional outcomes, they are associated with complications such as bleeding, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatory disorders. This has led to increasing development and use of less invasive treatment strategies including transurethral needle ablation, transurethral microwave therapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound, transurethral electrovaporization, water-induced thermotherapy, prostatic stent placement, as well as prostate artery embolization.

Most minimally invasive treatment strategies employed to treat BPH utilize a transurethral approach whereby tissue within the prostate alongside the urethra is intentionally damaged in an effort to decrease extrinsic pressure on the urethra. In contrast, prostate artery embolization (PAE) is a minimally invasive endovascular procedure in which the goal is to decrease blood flow to the prostate to induce ischemic necrosis and subsequently shrink the gland, thus reducing LUTS.

Procedural details

Prior to the PAE treatment day, patients will undergo an IV contrast-enhanced CT or MRI angiogram. The purpose of the CT or MRI is to define the arterial anatomy of the prostate and to identify potential arterial anatomic or atherosclerotic hurdles that may preclude or complicate the embolization.

PAE is performed in a hospital setting as an outpatient procedure. Once patients arrive in the hospital, an IV is placed within a vein of the arm. The IV is needed so that sedation can be administered during the procedure. In addition to the IV, a Foley catheter is placed within your bladder. This is done for your comfort during and after the procedure and to help the interventional radiologist more definitively localize the arterial blood supply to the prostate. Once these steps have been completed, you will be taken to one of the interventional radiology suites within the Department of Radiology. In the procedure room, a technologist will clean and prep both the right and left groin prior to start of the procedure.

The first part of the PAE procedure involves entering the arterial system of the body. This is most often done via the right common femoral artery, which is the artery responsible for the pulse that you can feel in the right groin. Local anesthesia (lidocaine) is used to numb the area surrounding this artery. Once the lidocaine has been administered, a very small incision is made in the groin and a small needle is placed into the common femoral artery. Once the needle is inside the artery, a wire is advanced through the needle into the artery. This allows us to remove the needle and place a catheter, which is approximately the size of a piece of spaghetti, inside the artery. An angiogram is then performed by injecting X-ray dye into the catheter. This allows us to see the arteries of the pelvis and determine where the left and right prostatic arteries are located.

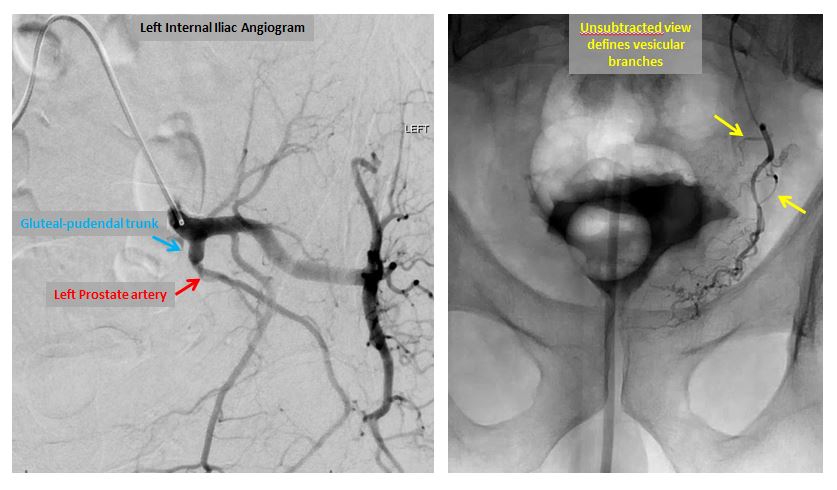

Left internal iliac (left image) and prostatic artery angiograms (right image).

Once the prostatic arteries have been identified, the catheter is repositioned under X-ray guidance and moved into the left prostatic artery. X-ray dye is again injected in order to confirm the position of the catheter. Once this is done, small particles or microspheres are injected into the catheter in order to stop the flow of blood within the left prostatic artery. Once it is injected, the microspheres induce inflammation, slow blood flow, and create clot formation within the artery. When blood flow has stopped within the left prostatic artery, the catheter is repositioned into the right prostatic artery and the procedure is repeated. In our experience, most patients can be embolized with a single catheter entering the arterial system on the right side; a second catheter placed into the left common femoral artery is necessary only in the most difficult cases. Once the embolization is complete, the catheter is removed and a seal is placed into the right common femoral artery to insure that there will be no bleeding from the site. The length of the procedure is variable and highly dependent upon the complexity of the arterial anatomy.

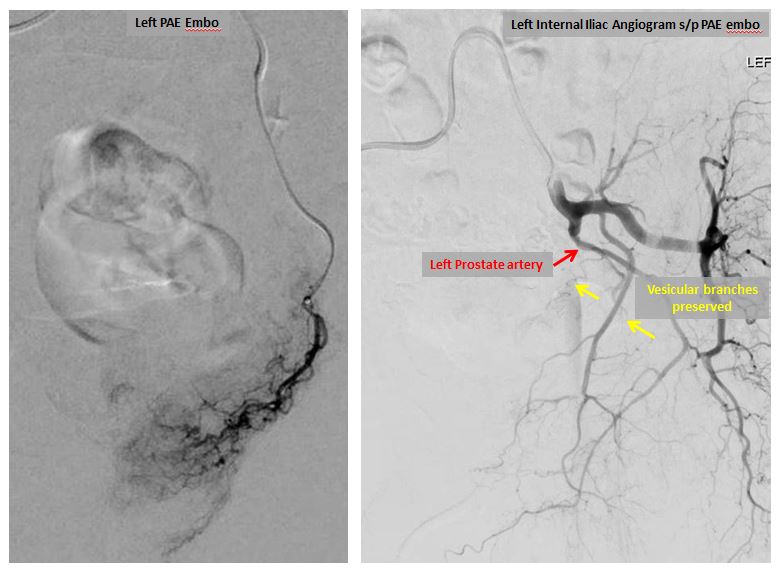

Left prostatic artery angiograms before (left image) and after embolization (right image).

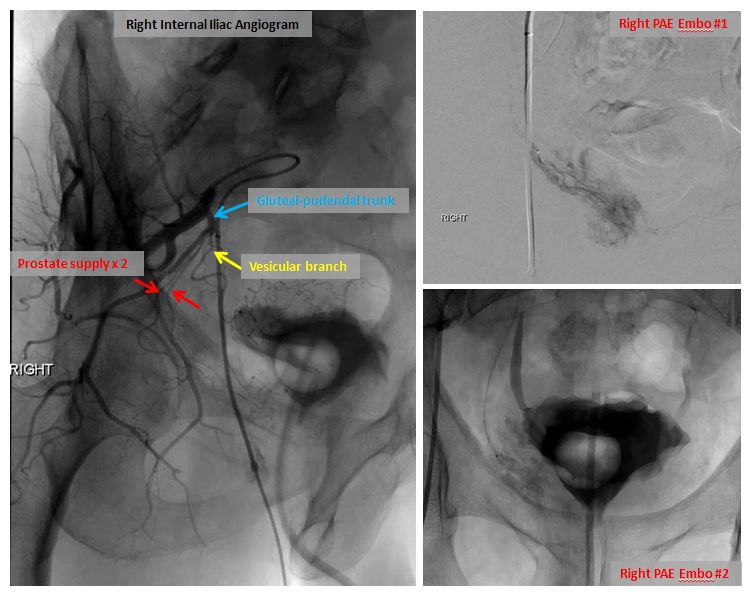

Right internal iliac angiogram demonstrating prostatic arterial anatomy with two arteries supplying the prostate (left image). Embolization images on right.

Results

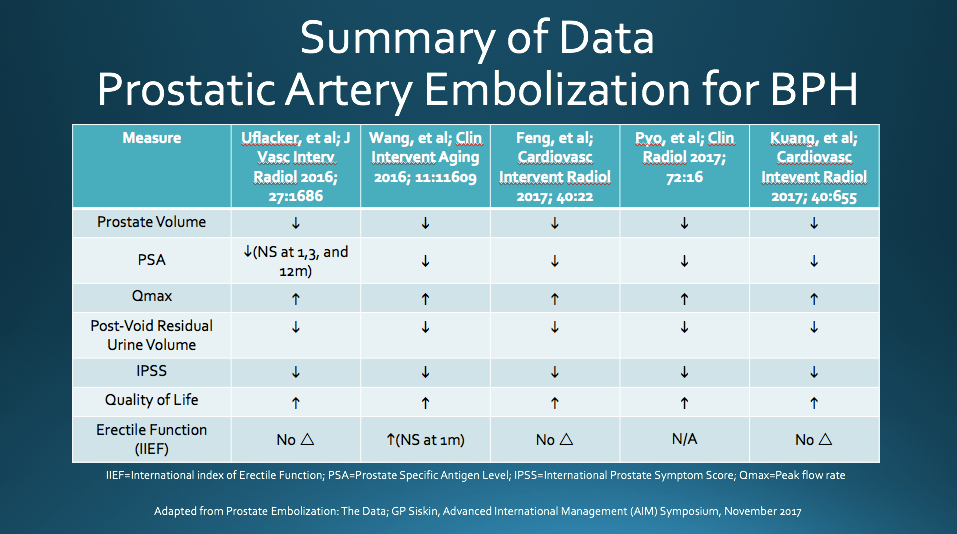

PAE has been shown to reduce patient’s International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and improve quality of life (QOL). The IPSS is a scoring system used to screen for and diagnose BPH, monitor symptoms, and guide management decisions. A study performed by Carnevale et al. demonstrated PAE clinical success rate of 91% and a found significant sustained improvement in IPSS following PAE [2]. Similarly, Pisco et. al studied 255 patients diagnosed with BPH and moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms who underwent PAE and found clinical success rates of 82%, 75%, 72%, and 72% at 1, 12, 24, and 26 months, respectively [3]. A recent meta-analysis of PAE for BPH, which included the aforementioned studies, found an overall decrease in IPSS of 13%, 15%, and 20% at 1, 6, and 12 months after treatment, respectively. The meta-analysis also found a sustained improvement in QOL following PAE [4]. See below for a summary of data from additional recent PAE studies.

It is important to remember that there are potential complications that all patients need to be aware of when considering PAE. The most frequent complications encountered following PAE are considered “minor” and include acute transient urinary retention, rectal pain, and painful urination. The prostate is in very close proximity to other pelvic structures, which can share arterial supply. Therefore, embolization of the vessels supplying the prostate may produce unintended ischemia of nearby structures such as the urinary bladder or rectum. The risk of unintended ischemia, or “non-target embolization” is significantly reduced with careful review of the pre-procedure CT or MR angiogram and meticulous catheter angiography during the procedure. Altogether, data indicates the overall risk of complications from PAE to be 33%, 99% of which are self-limiting and minor [4].

Potential Risks

References

1. Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Drake MJ, Madersbacher S, Mamoulakis C et al (2015) EAU guidelines on the assessment of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol 67(6):1099–1109.

2. Carnevale, Francisco C., et al. “Quality of Life and Clinical Symptom Improvement Support Prostatic Artery Embolization for Patients with Acute Urinary Retention Caused by Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia.” Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, vol. 24, no. 4, 2013, pp. 535–542., doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2012.12.019.

3. Pisco, Joao Martins, et al. “Erratum to: Embolisation of Prostatic Arteries as Treatment of Moderate to Severe Lower Urinary Symptoms (LUTS) Secondary to Benign Hyperplasia: Results of Short- and Mid-Term Follow-Up.” European Radiology, vol. 23, no. 9, 2013, pp. 2573–2574., doi:10.1007/s00330-013-2884-0.

4. Uflacker, Andre, et al. “Meta-Analysis of Prostatic Artery Embolization for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia.” Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, vol. 26, 2016, pp. 1686–1697.